Workshop

NeurIPS 2025

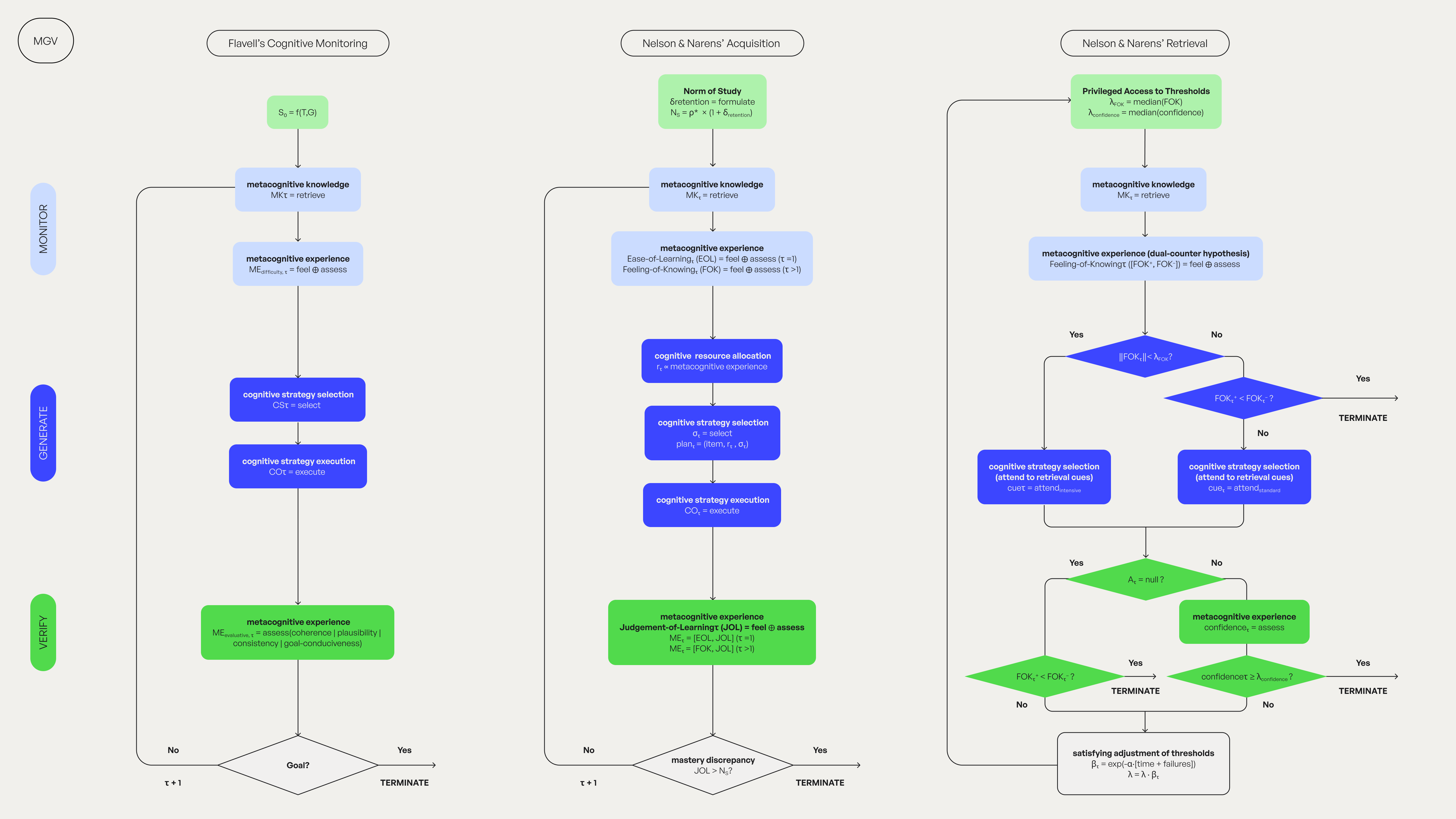

Monitor-Generate-Verify

There's a moment in every conversation with an advanced language model where it confidently explains its reasoning, and you realise it's lying. Not maliciously. It simply has no access to its own cognitive process. When your AI agent can't reliably monitor its own thinking, how can it know when it's uncertain, when it needs more information, or when it should refuse to answer? We went looking for answers in psychology papers from 1979. What we found was a blueprint that's been waiting 45 years to be translated into mathematics.

The Current Playbook Isn't Working

Recent advances in self-refinement models have predominantly adopted a Generate-Verify (G-V) structure to enhance reasoning performance through iterative feedback mechanisms. Think of G-V like drafting and editing: first you write something (Generate), then you review it for errors or improvements (Verify). If it's not good enough, you rewrite and review again, continuing this cycle until you're satisfied.

Despite these advances, G-V approaches share a fundamental limitation. They commence generation without first assessing task characteristics or retrieving relevant problem-solving strategies. Luo et al. (2025) found that models starting with the wrong approach suffer a 20% performance hit and rarely recover, even with multiple rounds of verification. They call it the 'prefix dominance trap'. Think of it as cognitive lock-in, where initial missteps become permanent despite repeated attempts at correction.

It's like trying to fix a wrong turn by driving faster. Once you're heading the wrong direction, no amount of acceleration helps.

Humans Don't Just Generate-Then-Fix

G-V assumes you can fix bad starts through better verification. But we don't just generate-then-verify. We monitor first, always.

In 1979, John Flavell laid out a theory of how metacognition works in humans. A decade later, Thomas Nelson and Louis Narens refined these ideas specifically for memory and learning Their frameworks describe metacognition as a control system with monitoring and control loops — where cognitive self-monitoring by higher-order processes generates signals for strategic control, forming continuous feedback loops between observation and control.

The key insight? Before humans tackle a problem, we assess it. We gauge difficulty. We retrieve relevant strategies. We consider our confidence. This all happens often below conscious awareness. But it happens. And it fundamentally shapes how we approach the task.

This metacognitive monitoring isn't perfect. Sometimes we're overconfident. Sometimes we underestimate difficulty. But having this system (even imperfectly) is vastly better than charging ahead blindly.

The Translation Project

So we did what engineers do when they find a good idea gathering dust. We tried to formalise it. To take Flavell's and Nelson & Narens' psychological theories and translate them into mathematical language that machines could, theoretically, implement.

The Monitor-Generate-Verify (MGV) framework attempts to capture what psychologists have observed. Think of it like this. Before you solve any problem, your brain runs a quick diagnostic. Monitoring is that moment when you look at a math problem and instantly know it's going to be brutal (what Flavell calls “feelings of difficulty”), instantly size up whether material looks learnable (what Nelson & Narens call “ease of learning”), or have that tip-of-the-tongue sensation where you know you know it (“feelings not knowing”). Generation takes those signals and decides what to do — should I work through this step-by-step or just move on? Finally, verification checks if it worked and files that information away for next time.

What We've Translated (And What We Haven't)

We thought we were being clever, packaging human metacognition into three sequential functions. But the problem is, thinking about thinking resists such tidy decomposition. The framework captures what happens when minds monitor themselves, but not the fundamental mystery of why there's something it's like to do so. We can architect systems that monitor their own processes, adjust strategies, and learn from outcomes. What we can't architect is the observer behind the observations — the part that experiences doubt, feels confusion, or recognises patterns with that peculiar sense of ‘aha’.

We're left holding a map of something we can't actually visit. What it does is map its contours and boundaries, translating Flavell's and Nelson & Narens' theories into the mathematical language needed to eventually bridge it. We've sketched rough maps of territory that's existed in human minds: territory that psychologists have been exploring for decades, which we're now trying to describe in computational terms.

In this work, we were more like translators, taking field notes written in the language of psychology and converting them into mathematical specifications. This is our earnest attempt at mathematising psychology — an interpretation that involved both necessary simplification and, we suspect, occasional overinterpretation of what Flavell and Nelson & Narens meant. But it's a start. A bridge between what we know about human metacognition and what we might build into machines.

Monitor-Generate-Verify represents theoretical work in computational metacognition. These are blueprints, maps with unexplored territories. Read the working paper for (in)complete mathematical specifications.

Built with theoretical rigour at socius: Experimental Intelligence Lab

Here's where we're supposed to end. But honestly? If you're thinking “okay, but does this actually work?” — we had the same question. We couldn't help ourselves. One weekend, too much caffeine, and a copy of Llama-3.1-8B later, we had our answer. It worked. (Sort of.)

Read how we implemented Flavell's theories in Before You <think> , monitor.